Literary Tropes

The interpretive mode feature of the Lone Woman and Last Indians Digital Archive highlights how and to what degree individual accounts of the Lone Woman’s story participate in the creation of a mythic narrative of the Lone Woman, the American Indian, and the encounter between white settlers and indigenous Californians. In doing so, it makes visible the utility of the Lone Woman story in reinforcing what scholars have termed "settler colonialism," the process by which settlers move into a colonial landscape and replace, literally and figuratively, the native inhabitants.1 Through a combination of deadly violence, forced relocation, and legal fiction, great numbers of the Native peoples of California disappeared in the nineteenth century, paving the way for the founding of white California and the proud celebration of its pioneers. The story of how the Lone Woman came to be the sole inhabitant of San Nicolas Island, how she came into contact with the hunting party of the Tennessee-born George Nidever in 1853, and how she arrived in, adjusted to, and died in Santa Barbara, California, is told many times in the documents constituting this archive. As one reads through hundreds of accounts of the story, the similarity of details reported becomes apparent. Each account draws from a selection of the following "plot" elements, with some including most of the details listed below and others containing just a few.

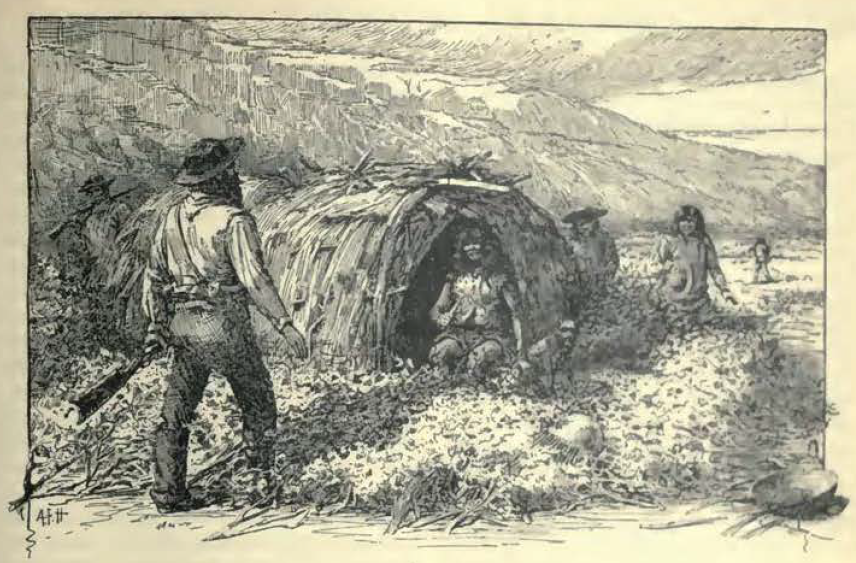

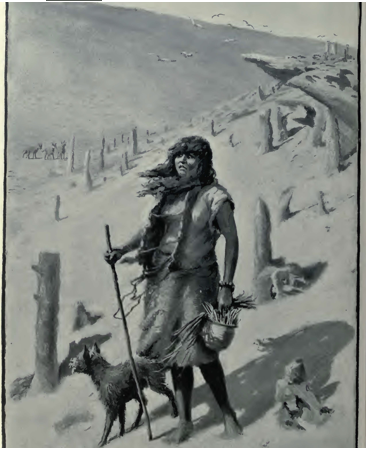

George Nidever "discovering" the Lone Woman, published in Californian Illustrated Magazine, 1893.

In 1814

- Confrontation between Alaska Native (Aleut or Kodiak) and Russian hunters and the Nicoleños

- The confrontation’s aftermath (e.g., slaying of the men, possession of the women)

In 1835

- Request for removal of the Nicoleños to the mainland (variously, by priests or government officials)

- Mechanism by which the Lone Woman was left on San Nicolas Island (e.g., jump overboard, "away at the mountains," went back for a child)

- The schooner Peor es Nada is not able to return to San Nicolas Island to collect the Lone Woman (it capsizes).

In 1853

- Priests request a search for the Lone Woman

- Searches fail to yield the Lone Woman but uncover signs of her continued presence on the island

- Successful search. The Lone Woman:

- Welcomes the party

- Offers food

- Packs up her goods

- Stops at water to wash

- Makes baskets

- The Lone Woman stays at hunters' camp

- Helps with various tasks (e.g., bringing wood and water)

- Spies a baby otter among the dead

- The Lone Woman "narrates" her story by signs

- European-style clothes are sewn for the Lone Woman

- The Lone Woman prays on the boat

- The Lone Woman confronts modernity (e.g., sees a horseback rider and/or wagon for the first time)

- The priests bring Indians to speak with the Lone Woman but no one understands her language

- The Lone Woman sings/dances/performs/interacts with visiting children

- George Nidever turns down offers to display the Lone Woman on stage or in circus

- The Lone Woman falls sick and dies

- The Lone Woman is conditionally baptized and then buried at the Santa Barbara Mission

- A representative selection of the Lone Woman’s personal items are sent to Rome

Literary tropes function as a tool that makes the Lone Woman’s story both familiar and exotic. The tropes also help to justify the action of both the American actors in the tale (the "rescuers" or "discoverers") and the American readers encountering the story in newspapers, magazines, scientific journals, and literature, an encounter that may take place days, months, decades, or even centuries (e.g., Scott O’Dell’s Island of the Blue Dolphins) after the events described. This makes good sense as a central feature of settler colonialism is its ongoing nature, its perpetuity. The political order established with the United States’ acquisition of California (1848) and California’s entry into the Union (1850)—events preceding the Lone Woman’s arrival on the mainland by just a few years—endures, structuring the lives of California’s Native peoples and defining the limits of their sovereignty, today as in the past.

First edition of Island of the Blue Dolphins (1960), published by Houghton Mifflin with cover art by Evaline Ness. (Courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

The Literary Tropes

Identification of literary tropes is interpretive rather than absolute, and the editorial choices made in this archive reflect this fact. At times, "plot" events are thoroughly entangled in a literary trope. For example: a document describes George Nidever’s search for the Lone Woman in language that closely echoes European explorers’ accounts of searching for, and finding, anticipated treasure. Nidever figures as Christopher Columbus, The Discoverer of the New World, if you will. At other times the presence of a literary trope is much more subtle—a narrative borrows descriptive sections from an earlier account about the Lone Woman and rewords those sections in a manner that softens the trope, making its presence less obvious. Finally, literary tropes may appear in accounts completely devoid of the larger context that makes them understandable. In other words, unless a reader is aware of the originating source—the earlier account(s) from which the descriptive section was taken—the literary trope is all but unrecognizable. In cases in which just a faint lingering of a trope appears—that is, the trope is identifiable as such only in relation to other narrations of the Lone Woman’s tale—this archive does not mark the trope. Additionally, this archive marks only those tropes that are both relevant to the Lone Woman’s story and pervasive. Tropes that appear only infrequently in the documents herein (e.g., the lazy Spaniard, as expressed by the idea that the Spanish word for tomorrow, mañana, translates to "never") remain unmarked.

Fourteen discreet literary tropes, discussed below, are flagged in the archive. The tropes are of two categories, those specific to the Lone Woman narrative and those that are common to the literature of settler colonial societies. The claim that after the 1835 removal of the Nicoleño people from San Nicolas Island, no boat was available on the entire coast large enough to make the return trip to collect the abandoned Lone Woman is an example of the former; the concept of the "vanishing Indian" and the particular claim that the Lone Woman was the "last of her race" are examples of the latter.

The tropes present in any given narration of the Lone Woman’s story can be seen by clicking the "Interpretative Mode" button underneath the digital surrogate (present in the left-hand panel of the webpage). The entire archive can also be browsed by literary trope, enabling a comparison of all uses of any one trope across time and place of publication. Finally, a series of data visualizations helps users to see when tropes first appeared, circulated, and declined in prominence; which authors and publications played the greatest role in embedding tropes within the Lone Woman narrative; and which tropes are the most, and least, pervasive.

As perusal of this archive makes clear, the use of literary tropes in the narration of the Lone Woman’s story had already stabilized by the 1840s. As early as 1847, newspapers reported that the Lone Woman took a dramatic jump overboard to swim back to San Nicolas Island’s shores, even as the rest of her people sailed to mainland California. This trope endured; in his author’s note to Island of the Blue Dolphins, Scott O'Dell confidently reports it as fact, while citing a historical source of indeterminate origin.

Tropes Specific to this Archive

Jump Overboard

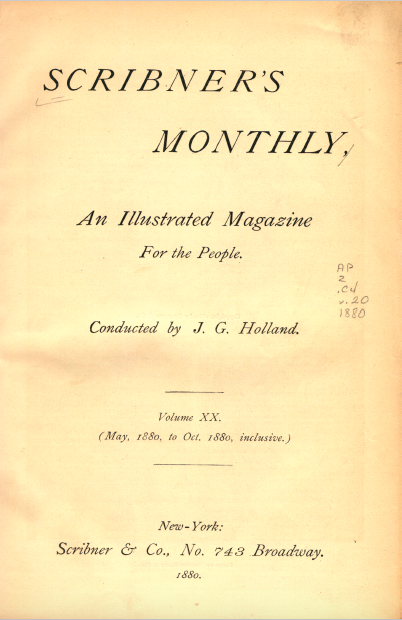

Although the earliest published narratives that offer an explanation of why one woman was left behind on San Nicolas Island provide a range of possibilities -- she was away at the mountains; she jumped overboard; she went to search for a child before boarding the ship and it left without her; she was accidentally forgotten on shore -- many accounts of the Lone Woman narrate a dramatic story of a frantic jump off the Mexican schooner Peor es Nada when it sailed from San Nicolas Island to San Pedro, California in 1835 with a small group of native islanders on board. The dramatic jump first appears in print in 1847, in a Boston newspaper. This Boston Atlas article is then reprinted in a Boston-based magazine (Littell’s Living Age) and in newspapers whose geography spans half the then settled parts of the United States—New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Wisconsin—and in far-away Hawaii. Not all reports of the Lone Woman’s story printed after the initial Boston Atlas article include the plot detail of the jump overboard, but many do. By the twentieth century, this explanation for the Lone Woman’s stranding on San Nicolas Island becomes dominant. Its spread is aided by the journalist Emma Hardacre, whose influential 1880 article about the Lone Woman in the nationally-circulating Scribner’s Monthly was frequently reprinted and the source of considerable borrowing. In fact, Hardacre was likely a key source for Scott O’Dell, author of Island of the Blue Dolphins (1960). In the novel's author's note, O’Dell affirms the veracity of the leap overboard, citing unspecified "reports from Captain Hubbard." No records of these reports have yet been found.

Emma Hardacre's influential article, "Eighteen Years Alone: A Tale of the Pacific," appeared in this issue of Scribner’s Monthly (1880) and helped popularize the "jump overboard" plot element of the Lone Woman story, making it a literary trope.

Why did the leap overboard become a dominant trope in the narrative of the Lone Woman? For one, it makes a good story! Sensationalism was a guiding principle of the nineteenth-century press, which did not require strict adherence to documentable facts. A blend of objective reporting, hyperbole, and fabrication, both within a publication and within an article, was expected. The particular invention of the jump overboard—a mother willing to risk her life by leaping into tumultuous waters to await, with her offspring, an uncertain rescue—also performs cultural work. Its sentimentalism facilitates readers’ identification as they sympathize with the Lone Woman—a fellow human being, parent, and mother. The (presumed) white readers’ identification with an Indian leads them, in turn, to view her as a Noble Savage. As such, the Lone Woman is a tragic figure destined to disappear.

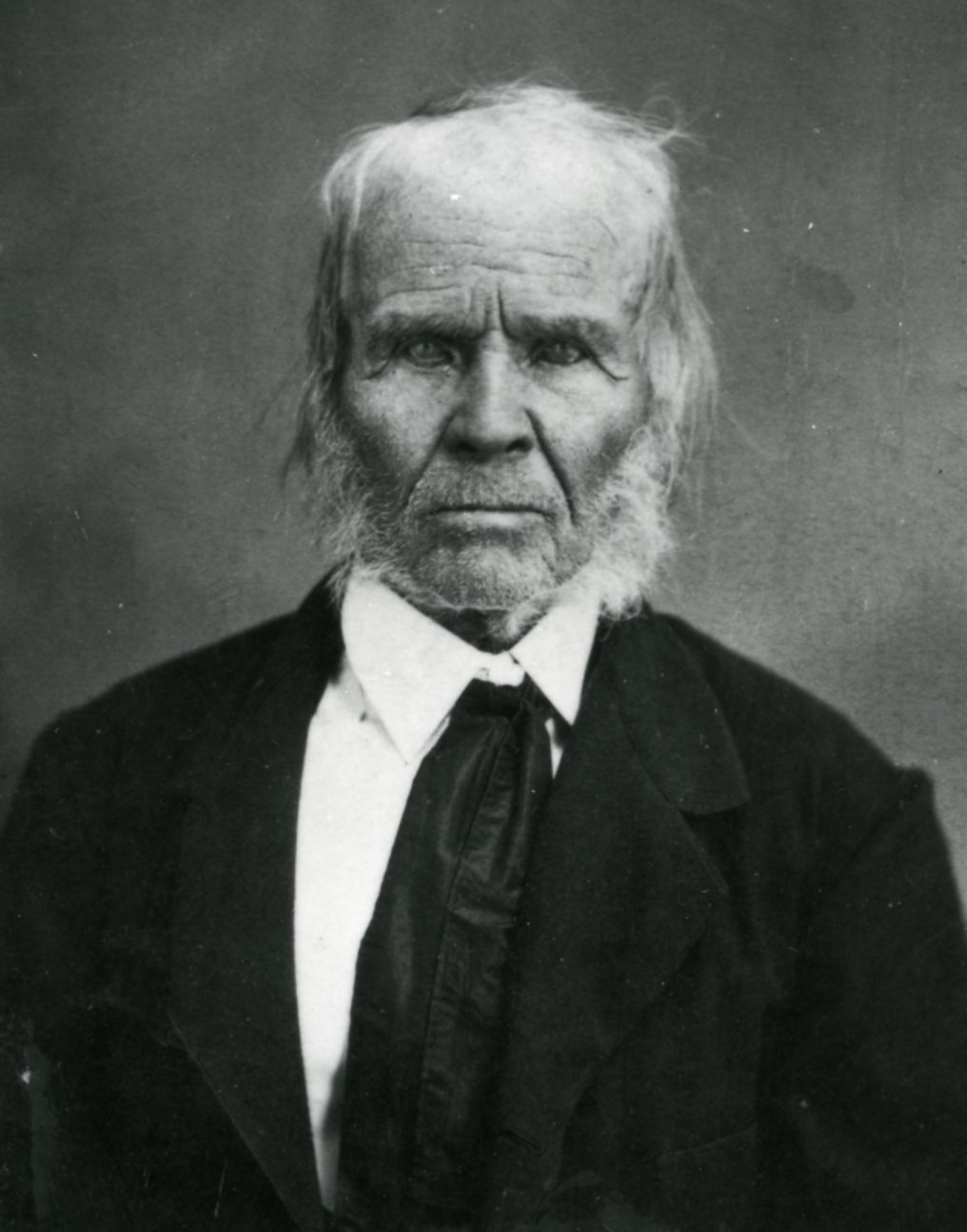

No Boat Available

As the story of the Lone Woman circulated, so too did the statement that, following the 1835 capsizing of the 20.5 ton schooner Peor es Nada, there was no boat on the California coast large enough to sail safely to San Nicolas Island.3 It was for that reason that no ship was sent to the island to bring the Lone Woman to the mainland, to join the rest of her people. The claim likely gained traction because it came from a source considered authoritative, George Nidever, the man credited with "rescuing" the Lone Woman in 1853. But Nidever may have made the assertion to excuse his own efforts to locate the Lone Woman earlier. As he reported in the life story he dictated to Edward F. Murray of the Bancroft history project (Life and Adventures of George Nidever), he engaged in a two-month otter-hunting mission aboard the Bolivar in the spring of 1843. According to ship records, the Bolivar Liberator (which had been renamed the Oajaca by owners Alpheus Basil Thompson and John Coffin Jones, Jr.) sailed to San Nicolas and San Clemente (both Southern Channel Islands) in 1843, with the crew taking twenty-one otters.4 Isaac Sparks, who had captained the Peor es Nada in 1834 and was likely on board during the 1835 removal of the Nicoleños from San Nicolas Island, was among the crew. Moreover, the thriving Pacific trade between California and the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) meant that many other large ships passed through the area as well; in his History of California, Hubert Howe Bancroft provides a list of 46 vessels sailing the coast in 1843.5 Given that a boat could have been sent for the Lone Woman, why did the statement that "no boats were available" become so widespread, beginning as early as 1856? The reality—that few Californians with the power and resources to minister to one Indian cared to do so—is harsh, and runs counter to the romantic, albeit tragic, narrative of Indian vanishing that many of the accounts of the Lone Woman sought to tell.

Universal Tropes

Anti-Russian Sentiment

California was divided between two colonial powers prior to US annexation: Spain and Russia. The former controlled more territory, sustained a longer occupation (approximately 70 rather than 29 years), and absorbed into its ranks substantially more US citizens, men who in fact facilitated the transfer of California to American hands in the mid 1840s. For all those reasons, the US state of California’s pre-history as "Alta California" has enjoyed a prominent role in historical narratives of the region’s history. It greatly overshadows the pre-history of the Russian American Company’s Colony Ross, a mercantile outpost for the maritime fur trade whose center was in Sitka, Alaska.

Russian America Company flag

The early historiography of California—that is, the earliest written history of California’s history—is dominated by Hubert Howe Bancroft, an American book collector and historian who employed scores of research assistants to aid him in the writing and publication of a seven-volume history of California (1886-90) and a one-volume history of Alaska (1886). Both were part of his much larger history of the west series. Bancroft’s history project, as it came to be known, helped to solidify the hero status of a number of Americans who emigrated to California during the Mexican period, and who became naturalized Mexican citizens in order to further their social and political advancement. When the United States annexed California, these American-born men became founding pioneers of the nation’s thirty-first state. George Nidever, the hunter credited with the "discovery" and "rescue" of the Lone Woman, is one such man. After his 1833 arrival in California, from Arkansas, he married Maria Sinforosa Ramona Sanchez and became integrated into Mexican society, raising Spanish-speaking children. But his Anglo name, native English language, and participation in westward migration also made him an ideal candidate for American pioneer status once California changed hands. An interview by one of Bancroft’s assistants resulted in his memoir, for which he is remembered: The Life and Adventures of George Nidever: A Pioneer of Cal. Since 1834.At the same time the historian Hubert Howe Bancroft romanticized the Spanish and Mexican periods of California history (albeit through the lens of Manifest Destiny), he painted an unfavorable picture of Russian rule in Alaska and northern California. In describing the sixteenth century, for example, Bancroft wrote: "The nation [Russia] could scarcely be placed within the category of civilization. While in Spain the ruling spirit was fanaticism, in Russia it was despotism." Bancroft wondered at Russian conquerors’ ability to overawe the natives: "that the aboriginal Americans should have ascribed divinity to the first Spaniards is not strange. They came to them from off the limitless and mysterious water in huge white–winged canoes, in martial array, with gaudy droppings and glistening armor; they landed with imposing ceremonies; their leaders were men of dignified bearing and suave manners, and held their followers in control. The first appearances of the Russians in Kamchatka [Siberia], however, presents an entirely different aspect; surely the Kamchatkans of the day were satisfied with ungainly gods."6 Bancroft’s unflattering portrayal of Russia as a nineteenth-century imperial power influenced both later historical treatments and popular understandings in California, creating the equivalent—or perhaps a transferring of—the Spanish "Black Legend" for Russians in the Americas.7 The term Black Legend, coined by Julián Juderías in his 1914 Le Leyenda Negra y la Verdad Histórica (The Black Legend and Historical Truth), describes a tradition of defamatory or propagandic writings that single out Spanish atrocities, characterizing them as crueler and more immoral by far than those of other colonial powers.

Photograph of Hubert Howe Bancroft, taken by the San Francisco photography studio Bradley & Rulofson. (The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection, POR 23. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

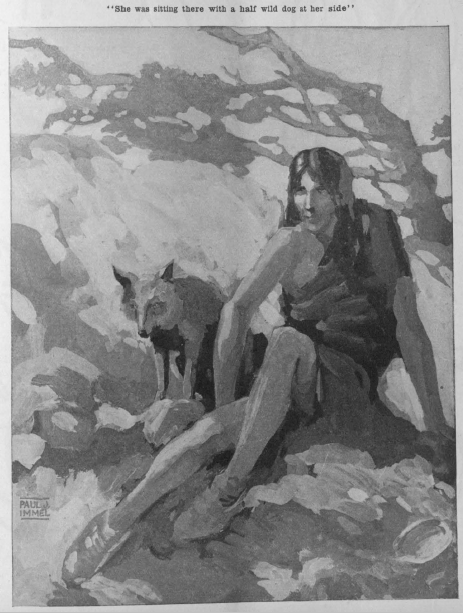

One place that the transference of the Black Legend to Russians becomes visible in a California context is within the Lone Woman’s story. The memoirs of George Nidever and Carl Dittman, a member of Nidever’s hunting party, describe the Lone Woman as surrounded by dogs when they first encountered her on her island; these animals, who promptly responded to her verbal commands, were pets. Later accounts of the Lone Woman, however, emphasize the wildness and savagery of the dogs that lived on San Nicolas Island with the Lone Woman. These were dogs present after the Russians began using the island as hunting grounds. Moreover, they assert that the Lone Woman communicated, in signs, that she feared that the wild dogs had eaten her child. This reading is captured in Island of the Blue Dolphins, Scott O’Dell’s 1960 fictionalization of the Lone Woman’s story: a pack of wild dogs kills Karana’s younger brother, and this pack is led by a foreign dog, an animal that arrived on the island with the Russians and Aleuts. Importantly, dogs played a role in the Black Legend. Sixteenth-century engravings by Theodor de Bry, for example, feature Spaniards setting war dogs upon defenseless adult Indians and feeding captured Indian babies to their hungry canines. In the Lone Woman story, these vicious Spanish war dogs, animals who will attack and eat humans, become Russian—a transference of the Black Legend to Russia.

Theodor de Bry engraving, 1594, depicting Vasco Núñez de Balboa setting war dogs on indigenous people of Panama as punishment for homosexual acts. (New York Public Library, Rare Book Room, De Bry Collection)

In the late nineteenth century, Bancroft and his American contemporaries tended to denigrate the Russians and romanticize the Spanish as predecessors to an American California. Many American men had arrived in California and married into the Californio elite (comprised of Spaniards and their descendants) before participating in political activities that eventually led to the annexation of the territory by the United States. Thus, the Spanish past became integrated into narratives of the American past in ways that the Russian past never did (for comparison, consider the way England dominates the American origin story in the east while the Netherlands barely figures in it). Popular historical narratives of California’s colonial period, long shaped by Bancroft, began to shift in the 1970s, however, as the "new social history" blossomed. Historians placed Indians, rather than the nation-state, at the center of their analysis, and they reevaluated the influence of California’s various colonizing powers on the land and its people.8 Using Russian as well as Spanish and Americans sources, they offered a different interpretation of the results: Russians were the least destructive of the colonizing forces in California.

When the Russian American Company (RAC) first established a colony in northern California in 1812, it was cognizant that Spain would perceive the move as a violation of its territorial rights. The RAC therefore proactively sought allies with the local population, arranging a treaty with the Kashaya Pomo and Bodega Miwok, whose homeland included the territory of the Russian Colony Ross.9 In doing so, the RAC asserted that the land on which it built was rightfully owned by the Native peoples, not Spain.

Once the RAC established its mercantile colony in California, it recruited and at times compelled Native peoples to participate in the Company’s hunting, agricultural, and manufacturing enterprises. Unlike the Spanish mission system, however, the Colony did not enact a program of enculturation, religious conversion, or Native relocation. For the most part, the local Pomo and Miwok people viewed the Russian presence as far more amenable than the Spanish. Visitors to the region, as well as the RAC agents, often contrasted the "magnanimous" Russians to the "cruel, tyrannical" Franciscans.10 And then, of course, the Russians left California entirely by 1842.

Discovery

When nineteenth and early twentieth-century journalists told the story of the Lone Woman’s removal from San Nicolas Island to Santa Barbara, California, they sought to make the story of the Lone Woman’s "rescue" as dramatic as the story of the Lone Woman’s survival. To do so, they turned to the trope of discovery, remaking sea otter hunters George Nidever and Carl Dittman as modern-day explorers, a nineteenth-century Christopher Columbus or Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, if you will (Cabrillo was the first European to set foot in present-day California). In these journalists’ telling, Nidever and his men don’t merely find the Lone Woman, they discover her. Doing so requires knowledge, wit, and skill: first the Lone Woman’s footprints are detected, then the objects filling the Lone Woman's basket are scattered, and finally, on a third expedition, the Lone Woman herself is stealthily approached and secured.

George Nidever, sea otter hunter who brought the Lone Woman to Santa Barbara and whose life story has been published as The Life and Adventures of George Nidever. (Courtesy of Santa Barbara Historical Museum)

The trope of discovery is rhetorically linked to possession; in discovering new lands, Europeans also laid claim to them. Similarly, in discovering the Lone Woman, Nidever not only laid claim to her (she would spend the remainder of her short life in his household in Santa Barbara, under his wife’s care), but also, on behalf of the United States, he laid claim to her land. The Lone Woman was the last California Native to live on San Nicolas Island. With her removal, the land came into the full possession of the United States. Today, the entire island is under the control of the US Navy and it is used, among other purposes, for weapons testing.

Girl Crusoe

Daniel Defoe’s The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner draws inspiration from the historical stranding of Scotsman Alexander Selkirk on an isolated island in the Pacific. First published in 1719, Robinson Crusoe Crusoe is among the most widely published English-language novels of all times. Not long after it was published, and continuing into the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of “female Crusoe” stories appeared in print, both in newspapers and as “memoirs.” Nineteenth-century readers who encountered the story of the Lone Woman would have been familiar with Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and likely with “female Crusoe” tales as well. Perhaps, then, a comparison between the Lone Woman and Crusoe was inevitable. But there is a great irony in imagining an island Native as a Robinson Crusoe figure. Defoe’s protagonist is a British owner of a Brazilian plantation; he shipwrecks en route to Africa, where he intended to buy slaves. Once stranded in the South Pacific, Crusoe acts as any good colonialist would: he begins "improving" the land, of which he declares himself "king."

The Lone Woman as a female Crusoe, published in Californian Illustrated Magazine, 1893.

When Crusoe sails for Europe at the end of the narrative, he does so with money in his pocket, a Native servant (with whom he initially communicates through signs) by his side, and land in his possession. Moreover, he leaves behind a group of loyal subjects who will enrich his holding from afar, as colonists. Crusoe and the Lone Woman’s island experience couldn’t be more different! While the former was a perpetrator and beneficiary of colonialism, the latter was its victim. In leaving her natal home, the Lone Woman forfeited the island’s wealth to her acknowledged conquerors. Hunters, sheep herders, amateur anthropologists, and ultimately, the US Navy, took possession of San Nicolas Island and all it holds. The Lone Woman, in turn, became a refugee who lived just seven weeks on US soil.2 She was buried under a foreign baptismal name and one of her prized cormorant skirts was purportedly sent to the Vatican, evidence of Europe’s success in "civilizing" the New World.Indians as Savage

The trope of the Indian as an evil, cruel, savage human being who observes no rules of decency—torturing, raping, murdering babies, even engaging in cannibalism—dates to the earliest European contact with the Native peoples of the Americas. It gained force during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries when the expansion of European settlements increased tension between new arrivals and the Native peoples whose land they annexed and lifeways they threatened. As colonists were drawn into all-encompassing Indian wars, violence—and stories of this violence—arrived at settlers’ doorsteps. In Anglo-American narratives of Indian savagery, including the pervasive captivity narrative, those Indians aligned with foreign powers, the (Catholic) French and Spanish, were deemed especially prone to cruelty. During the nineteenth century, Anglo-American narratives of captivity, torture, and barbarism moved west, as did the battles of Indian resistance.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century narratives of the Lone Woman collected in this archive, it is the Indians under Russia rule who are most frequently aligned with the savage Indian trope (see Anti-Russian Sentiment, above). According to these reports, the Kodiak Island Natives (who are sometimes misidentified as Aleuts) not only slaughtered all able-bodied men on San Nicolas Island, but they also take the island’s women as their own—then callously abandon them to their fate when their Russian masters return to the island to collect them. Also associated with savagery, if less frequently, are the ancestral predecessors of the Nicoleños, people who are more typically depicted as Noble Savages.

Indian Queen

Beginning in the fifteenth century, as Europeans embarked on voyages of discovery and exploration, they created visual allegories as shorthand representations of the continents—and people—they encountered during their travels: America, Asia, Africa, and Europe. These visual images, European imaginings of the world, became cartouches decorating newly mapped lands as well as stand-alone paintings, engravings, tapestries, and statues. Individual depictions of the continents varied by artist and evolved over the nearly 500 years of their creation, but they share common elements. Each continent is represented as a young, fertile woman—a queen—surrounded by the riches of her land. While the young woman representing Europe is fully clothed and often holding the trappings of civilization (and domination)—a scepter, a book, a globe, a crucifix—America is invariably nude. The openness of her youthful body, the suggestion of fertility and availability, mirrors European imaginings of the "Virgin Land" she represents, a territory ripe for Europe’s taking. As America, the embodiment of the land, the Indian Queen is in a position to bestow the gifts she clutches—the gift of herself and the flora and fauna of her homeland. Yet European fears are also reflected in their fanciful imaginings. America is regal in bearing, whether sitting, standing, or reclined upon a hammock, but she is also associated with barbarity. She may hold a weapon of war, for example, and a severed head or leg that hints at cannibalism may lie near her feet. America, in short, is in need of Europeans’ civilizing impulses.

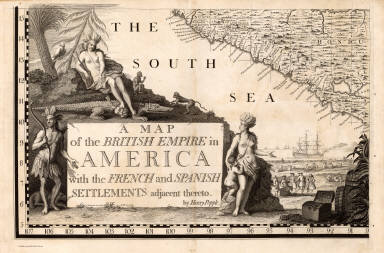

Henry Popple, A Map of the British Empire in America with the French and Spanish Settlements Adjacent Thereto, Detail (London, 1733). This large map was widely distributed and admired for its beauty. The Indian Queen, America, reclines with one foot resting on a decapitated head (symbolizing cannibalism) and the other on an exotic animal, the alligator.

In a number of documents within this archive, the Lone Woman figures as the Indian Queen, an allegorical representation of America. Textual details including descriptions of her dressed in a feathered garment, surveying the land, regally welcoming long anticipated visitors, and serving her guests from the bounties of the island all echo visual elements of the allegorical four continents. The Lone Woman’s willingness to be "discovered," "civilized" (clothed in European dress, fed with European foods), and brought away from her homeland must be understood in light of her representation as the land and its riches. (It is this same duality that gives the Lone Woman power to stop the wind through prayers: she is the land, the wind, the natural world.) In many narrations of the story, the Lone Woman gives herself to her "rescuers," her captors, as the Indian Queen. In taking the Lone Woman to Santa Barbara, California, Nidever and his men reproduce the discovery of America.

Lazy Indian

The idea that the Indian was lazy first emerged in the seventeenth century and was closely tied to English conceptions of proper gender roles: men should till the land and women complete less onerous, indoor work. When the English in Virginia observed Powhatan men engaged in hunting and fishing—the former considered by the English an aristocratic pastime, not work—they deemed Indian men "indolent" (and the Indian women who cultivated the land "drudges.")11

The stereotype of the "lazy brave" and "squaw drudge" not only persisted in the centuries that followed, but in fact became more entrenched. In the east, the idea that Native peoples did not "properly" use the land—that is, cultivate it for agriculture in ways recognized by American settlers—helped to justify Indian Removal. The Cherokee are illustrative. Until the late eighteenth century, farming among the Cherokee, a matrilineal society, was "women’s work" that bolstered women’s power. Women were in charge of the production and distribution of agricultural products whereas men were in charge of the production and distribution of meat obtained through hunting. In American observers’ eyes, however, Native land cultivation was discounted because it was performed by the "wrong" gender. In the early nineteenth century, as the Cherokee faced new incursions on their territory, including lands they had cultivated, they engaged in a restructuring of their society in order to appear more aligned with the patriarchal settler society that surrounded them.

Digger Indians, Yo Semite Valley, by John P. Soule. Published in Boston, 1870. Stereograph card — a pair of photographs designed to create the illusion of three dimensions when viewed through a stereograph. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Divsion, LOT 11958-21, no. 32 [P&P])

Even as a matrilineal clan-based governance structure was replaced with a bicameral legislature with elected male leadership, the rhetoric of the "lazy Indian" who failed to cultivate the land endured, and it justified Indian Removal. By the beginning of the twentieth century, this logic was commonplace. Theodore Roosevelt, for example, wrote that "the man who puts the soil to use must of right dispossess the man who does not, or the world will come to a standstill."12 As American settlers moved west throughout the nineteenth century, they encountered Native peoples who practiced different subsistence strategies—ones anthropologists would later label "hunter-gatherer." These Native peoples actively shaped their environment (e.g., by use of fire) to maximize yields of natural resources. But by categorizing their food production as gleaning from, rather than "improving," the land, settlers could justify their seizure of Native soil. In central California, for example, American miners used the derogatory term "Digger Indian" to describe peoples who obtained a substantial portion of their caloric needs through indigenous vegetation, including acorns and roots. In the view of miners, California Indians—the descriptor was soon applied to all Native people, regardless of subsistence methods practiced—failed to use the land properly. They could therefore be displaced. In the Lone Woman and Last Indians Digital Archive, the Nicoleño people are often described as "subsiding solely on fish"—in other words, as people who glean from rather than improve their natural environment. The trope of the lazy Indian also appears in reference to the Lone Woman specifically; she is described as flitting from one task to another without completing anything (e.g., abandoning basket-making without any one completed basket but with many in process).Noble Savage

The term Noble Savage became part of European explorers and settlers’ vocabulary for discussing the indigenous peoples they encountered in the New World, and the term continued circulating widely throughout the early twentieth century. As racial and ethnic "others," Indians were alternatively celebrated and vilified, as the contemporary meaning of the two words comprising the term Noble Savage reflects. The particular contours of settlers’ views of actual Native peoples fluctuated over time and across space as Europeans (and later, European-Americans) and Natives competed for land and other resources, processes that inevitably brought conflict and violence. But the term and image of the Noble Savage endured. The eighteenth-century Romantic movement fostered in Europeans on both sides of the Atlantic a high regard for proximity to "unspoiled nature." Indians, viewed as unburdened by the trappings of civilization that alienated one from the natural, became prized for their purity and innocence. Rhetorically, Noble Savages presented a means of critiquing European decadence. Yet the obverse side of these positive associations remained: being untutored and untamed by Christian teachings, Indians were also viewed as having fewer constraints against brutish or barbarous behavior. Ferocity in war and cruelty enacted in the name of honor were compatible with Noble Savagery. Noble savages had savage virtues, but also savage vices.

Nineteenth-century paintings such as Thomas Cole’s The Savage State (from his Course of Empire) illustrate this dual imagining, as do novels by James Fenimore Cooper. When actual Native peoples were removed from the landscape of the Eastern United States during the mid-nineteenth century and no longer a threat to settlers, the concept of the Noble Savage reemerged with force. Noble Savages, now vanished, could be celebrated as American heroes with town streets named after chiefs and romantic statues of Indians erected on village greens.

The Savage State (1834) by Thomas Cole, from his The Course of Empire. (Oil on Canvas, 39 ¼ x 63 ¼ in., Object no. 1858.1, Collections of the New-York Historical Society. Used with permission)

A cluster of sometimes contradictory traits characterizes the Noble Savage trope. Simple and magnanimous, he is nonthreatening and sometimes childlike in his behavior. Yet the Noble Savage is also stoic and brave, a man admired for his strength and daring. While unschooled in Christian ways, the Noble Savage’s high social instincts nevertheless lead her to be a gracious host. A fair complexion, moreover, might make the Noble Savage appear nearly white, nearly "one of us."Savagery of any kind is deemed incompatible with civilization, however, so Indians taken outside their natural habitat are understood to waste away. Whereas "bad" or ignoble Indians become degraded—pitiful shadows of their former selves—when removed from their natural habitat, Noble Savages "droop" under civilization; they resist degradation but waste away in death.

Origins

Nineteenth and early twentieth-century Americans eager to establish themselves as founders of a new civilization, the legitimate heirs to the land of a "vanished" people, became deeply concerned with origins, the peoples and cultures that populated the land before them. Turn-of-the-century archeology and historical preservation, as practiced by both amateurs and, often, professionals, represent two manifestations of this impulse.

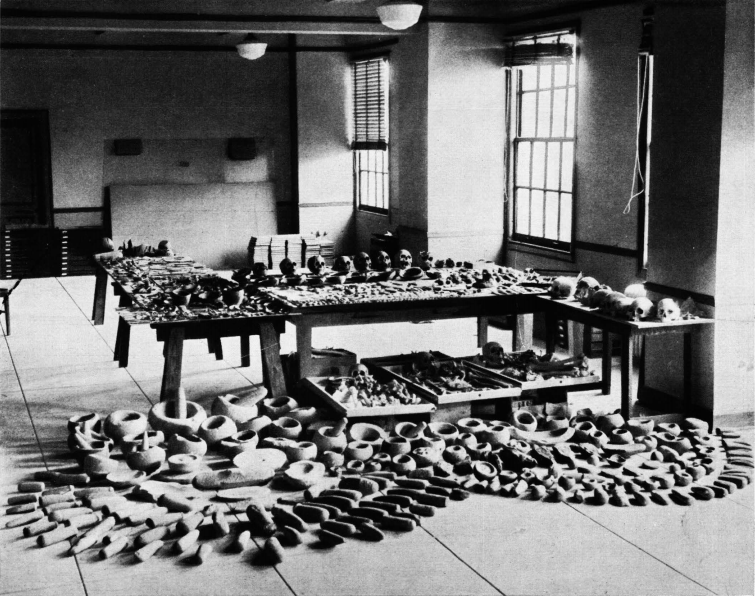

The artifacts and ethnographic objects uncovered by archeological digs on San Nicolas and other California Channel Islands were sent to be displayed in museums and detailed in reports of learned societies (e.g., the American Anthropological Association), but they were also described in newspapers and popular periodicals. In these publications, the physical vestiges of earlier people, whether bones and burial sites, tools, or weapons, are frequently couched in the language of wonder. Skulls are unusually large, skeletons lie in the jaws of whales, etc. And in each case, the bones are "ancient," the remains of an "extinct" people. This temporal distancing allowed the archeologists who participated in the uncovering to claim the land for themselves: through digging, they became heirs to the bone-filled land. In the process, however, present-day Native peoples were erased as the legitimate landholders—and guardians of the remains of people they considered ancestors and kin.

Historic preservation and commemoration provided another route for Anglo-American settlers to claim their place in the west by means of their predecessors. The Society of the Native Sons of the Golden West, a patriotic and mutual aid society, formed a historical landmark committee and was instrumental in preserving early Spanish architecture in California. Their founding mission statement speaks of perpetuating in native Californians "the memories of one of the most wonderful epochs in the world’s history—"the days of ’49."13 But in addition to preserving and interpreting historic sites related to the Gold Rush, the Native Sons sought to protect the Spanish missions, their pre-history. Like Indian artifacts, Spanish edifices, despite their recent provenance, might be described as "ancient" (see, in this archive, Fred Spalding Witter’s 1885 article "Sanitarium of the West" in the Rochester (NY) Democrat and Chronicle, and its many reprints). The Spanish, like the Indians, were seen as part of a romantic past, an older era that set the stage for the California pioneers. (See also Anti-Russian Sentiment, above)

Photograph from Bruce Bryan’s article, "San Nicolas Island, Treasure House of the Ancients: Part I," published in 1930 by Art & Archaeology. (Used with permission)

Signs Easily Interpreted

Although people speaking a number of different Californian and European languages attempted to communicate with the Lone Woman orally, no one was found who could understand the woman’s language well. As reported in newspaper articles about the Lone Woman and in the notes of anthropologist John Peabody Harrington (1884-1961), who interviewed a number of elderly California Indians who were alive when the Lone Woman was brought to Santa Barbara, California Natives emphasized their inability to understand the Lone Woman completely.14 Father Sanchez, who baptized the Lone Woman on her deathbed, moreover, did so conditionally, presumably because he could not determine through speech whether the woman had previously been baptized. By contrast, American pioneers who communicated with the Lone Woman through makeshift hand signals and signs often declared their ability to "readily understand."

Reading the accounts of colonizers for information about indigenous experiences is always challenging given the power differentials and worldviews separating interviewer from interviewee. But when makeshift signs, rather than a mutually intelligible language, are the primary means of communication, understanding becomes even more suspect. In this case, language barriers are added to cultural hurdles. Yet many Californian settlers who interviewed the Lone Woman were so eager to understand her extraordinary trial that they convinced themselves of their ability to comprehend. In this regard, they mirror early European explorers like Columbus, who claimed that they understood Native people’s signs perfectly.

Those who interpreted the Lone Woman’s signs may have believed that they "knew" what Karana experienced in part because they were familiar with romanticized tales of shipwrecks such as Robinson Crusoe. (For this reason, the "signs easily interpreted" and "girl Crusoe" tropes often appear together.) Inherent in their confidence of understanding, however, is the imposition of a European worldview: they assume that the Lone Woman’s experience of isolation and survival would mirror their own, or, that they know the "nature" of the Native so well that they could comprehend how an Indian would experience the trial.

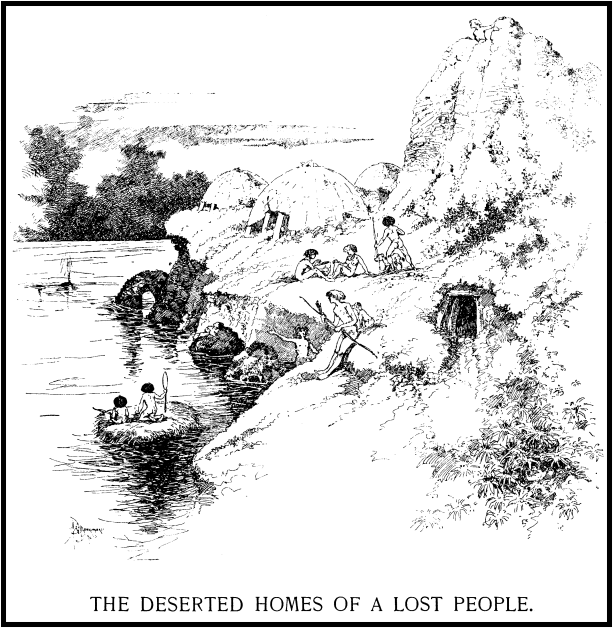

Vanishing Indian

Photograph from "The Deserted Homes of a Lost People: The Santa Barbara Channel Islands" (1896) published in Overland Monthly, 1896.

Through a complex political and cultural process, nineteenth-century Americans recreated themselves as indigenous to the frontier lands of the United States by removing the people who were actually native to the landscape. This centuries-long project took multiple forms. The most visible component of Indian vanishing is physical removal: indigenous populations within the United States declined through exposure to European diseases and involvement in European warfare, both of which resulted in great numbers of death. But Indians also receded from the landscape by means of federal policy. War treaties signed after tribes lost battles of resistance forced a number of Native peoples to cede homelands in the eastern half of the United States, "disappearing" to as yet unsettled land in the west. Federal legislation such as the 1830 Indian Removal Act (which led to the infamous Trail of Tears) accomplished similar ends, placing Native people on western reservations. As a result of disease, warfare, and the physical removal of Indians from the eastern half of the United States, then, American settlers living in New England, the Southeast, and the Midwest experienced Indian "vanishing" during the nineteenth century.

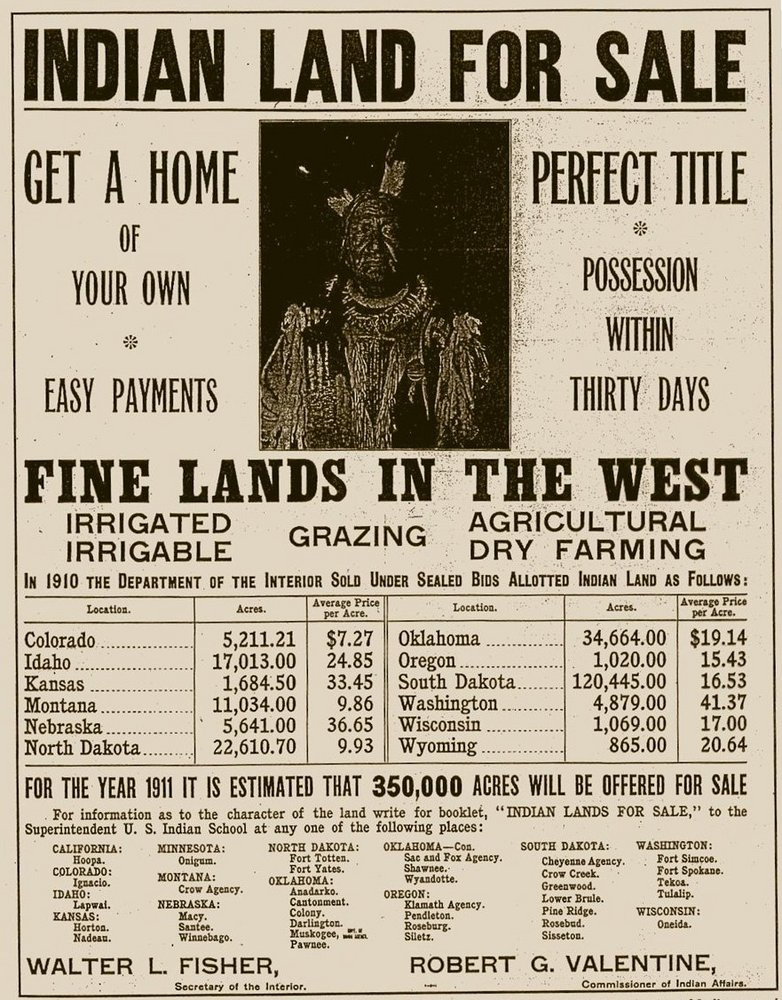

But Indian removal involved much more than the physical displacement of indigenous bodies. During the second half of the nineteenth century, Native peoples were also "removed" from the landscape via federal polices rooted in the construction of cultural and legal identities. Forced assimilation (e.g., residential boarding schools that worked to destroy Native languages and kinship ties in youth) was aimed at cultural eradication of the Indian. Simultaneously, policies of detribalization used US federal law to declare particular groups of Indians no longer in existence. Communal land was redistributed via the 1877 General Allotment Act ("The Dawes Act") and individual Indians converted into US citizens, without the unique rights and privileges due a sovereign people.

US Department of the Interior advertisement. After Indian land was divided into 160-acre individual family allotments under the Dawes Severalty Act (1887), the "extra" land was sold to settlers. The policy attempted to force assimilation and weaken tribal sovereignty.

The California StoryTracing the contours of Indian vanishing in California is particularly complex and does not always conform to national patterns.15 During the pre-contact period, California boasted a uniquely dense and diverse Native population. Post-contact, California Indians interacted with multiple colonial systems—Spanish, Mexican, Russian—before being incorporated within a politically mature United States. During both the Mexican and American periods, land enclosures by individual settlers displaced California Indians from their homelands, and the violence that resulted led to the outright extermination of many Native peoples. By the time California entered the Union, in the Gold Rush’s wake, conflict over land and other resources was ripe. There were no "open" or "unsettled" lands farther west upon which California Indians could be relocated, and US policymakers met strong settler resistance when they attempted to declare areas of California off-limits to fortune seekers and self-proclaimed pioneers.

Some groups of Native Californians did acquire federally-recognized reservations in the early twentieth century but many others did not. The nature and duration of colonial contact with Spanish or Russian powers played an important role in shaping tribal groups’ relationship with the United States after California statehood.16 For example, those coastal tribes that had been most deeply entangled in the Spanish mission system were not recognized as ethnographically distinct by nineteenth-century US policymakers, and they failed to obtain federal recognition and land. Like the twentieth-century US residential Indian boarding schools that would follow, Spanish missions sought to eradicate tribal culture and undermine tribal authority. The success of these goals had long-lasting ramifications when California, and its Native peoples, came under US jurisdiction. Because they were recognized as indistinct "Mission Indians" rather than as members of a distinct Native tribe brought to a Spanish institution, those groups subjected to near-complete missionization were denied treaty-making powers in the nineteenth-century United States. Subsequently, they have not been able to demonstrate continual tribal political authority from the pre-contact period to the present (Mission Era inclusive). As a result, they have become "unacknowledged tribes"—tribes that lack federal recognition to this day.17 Declared "extinct," these tribes "vanished" in the nineteenth century even as their members remained alive and well aware of their heritage (in fact, today, many unacknowledged tribes are actively seeking federal recognition from the US government).

Illustration of the Lone Woman, from "The Lost Woman of San Nicolas," published in Touring Topics, 1928.

It should be noted that the field of anthropology played a critical role in the process of declaring particular Indian tribes extinct. Native peoples subjected to the mission system in California "vanished" in part because anthropologists—and most importantly Alfred Kroeber, the founder of the University of California, Berkeley’s anthropology department—determined their unique cultures to be so thinned by assimilation that they no longer qualified as distinct tribes. Kroeber and his colleagues held largely essentialist views, deeming California Indian culture more or less static prior to European contact. The greater an individual Native group’s exposure to new ideas and lifeways via Europeans and other tribes in mission centers, the less authentic their cultural practices were viewed by anthropologists in the early American period. Mission Indians forged new identities; they were still Native identities, but they were not identical to those of their ancestors. According to Kroeberian logic, these new identities were less Indian, and they meant that the originating tribes had ceased to exist.

Vanishing as Literary TropeBoth in California and throughout the United States, vanishing took one final form – in popular culture. Novels such as James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans (1826) provide a clear example of the phenomenon: descendants of the Mohicans fictionalized by Cooper continue to flourish today as the Brothertown Indian Nation. The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island has similarly been proclaimed the "last" of her tribe, as the documents in this archive attest. Her kin, the people removed from San Nicolas Island on the Peor es Nada in 1835, were presumed dead in 1853, when no one could be found who could fluently communicate with the Lone Woman. In some narrations of the Lone Woman’s tale, authors use the capsizing of the Peor es Nada—which took place at the entrance of San Francisco Bay after dropping off the Nicoleños in San Pedro—as a means of declaring the death of the entire people, minus the Lone Woman. Other narrations suggest that the islanders transported on the Peor es Nada arrived safely on the mainland but soon after sickened and died. Historical records tell a different story. In 1853, when the Lone Woman arrived in Santa Barbara, at least one man removed from San Nicolas as a child was still living in Los Angeles, married to a California Indian.18 And given his age, it is likely that he fathered children. Regardless, other descendants are probable as it is highly likely that there were smaller migrations from San Nicolas Island to the mainland prior to 1835. The Lone Woman’s death, therefore, did not mark the "end of a race," or of a culture, as so many news reports proclaimed.

Wild Child

Wild, or feral, children have a long history in Western myth and folklore. A Wild Child might be the offspring of gods and animals, or he might be a human child nursed by an animal family. In Roman mythology, the twin brothers Romulus and Remus—the children of a human and a god—provide one example. Abandoned at birth, the boys were discovered by a wolf, who nurtured the infants until a shepherd took them under wing. As an adult, Romulus founded the city of Rome—which takes his name—at the site of the wolf’s deliverance.

During the eighteenth century, the narrative of the Wild Child entered the literature of science. Carl Linneaus, the so-called Father of Taxonomy, sought to make sense of recurring stories of real-life "wild men." Based on nine case studies ranging from 1344 (a Hessian wolf-boy) to 1731 (the Wild Girl of Champagne), Linneaus devised a species distinct from the Homo sapien, the feral man: Homo ferus.19

The Wild Child was particularly interesting to Enlightenment thinkers because he presented an instance of "natural man" untainted by civilization. (The connection to the Noble Savage is readily apparent.) Free from the constraints of socialization, wild children provided a blank slate upon which one could study human development, including the acquisition of language and social manners. As a subject of pedagogical remediation, the Wild Child became a mechanism of asserting the redemptive force of civilization and culture.

While the cases upon which Linneaus based his species are rooted in Europe, the narrative of the feral child shifted to colonial settings in the nineteenth century—India, Africa, and as we see in the case of the Lone Woman, America. In narratives such as Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Books (1894-95), civilization’s redeeming powers in the face of wild children such as the wolf-boy Mowgli become a means of justifying, and indeed celebrating, imperialism.

Nineteenth and early twentieth century accounts of the Lone Woman frequently invoke the trope of the Wild Child. Some narratives remark that the Lone Woman was not "wild;" despite the fact that her language was incomprehensible to those with whom she came in contact, her social graces were fully intact. In other accounts, however, the Lone Woman is cast as a Wild Child. In these tellings, years of isolation on the desolate San Nicolas Island, with only animals for company, doomed the Lone Woman to perpetual bestiality. The central marker of her animal-like status is her inability to speak, the fact that she has forgotten her native tongue. Positioning the Lone Woman as a Wild Child, either by association or disassociation, reinforces the benevolence of Americans’ efforts to rescue her from her native land and bring her to civilization.

Illustration of the Lone Woman, from "The Lost Woman of San Nicolas," published in Touring Topics, 1928.

Wonder

Beginning with Christopher Columbus, the first Europeans to encounter the Americas in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries used the language of wonder to describe what they saw, heard, smelled, and tasted in the strange new land upon which they had arrived. The New World presented a land entirely absent from the European worldview—America, unlike Europe, Asia, and Africa, is mentioned nowhere in the Bible. The Americas and all they held were startling to Europeans. Wonder, as literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt has argued, became the primary means of articulating what Europeans felt and thought in the face of the "radical difference" they confronted.20 By invoking wonder, European explorers declared their experiences real, even when they seemed unbelievable. Wonder functioned as a kind of momentary paralysis during which the observer might struggle to categorize that strange new sight that he confronted: was it good or evil? Wonder encompassed both: the marvelous (e.g., exceedingly large fruit, intensely beautiful landscapes) and the monstrous (e.g., human beings with tails). A number of journalists who wrote about San Nicolas Island and the Lone Woman in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries adopted this centuries-old concept of wonder, along with its language of the marvelous and monstrous. That they did so may seem strangely antiquated until one considers their task: telling an unbelievable narrative, the story of a Native woman living utterly alone on an island, for eighteen years, and then, more than a decade and a half after she was supposed dead, European-Americans finding traces of her existence: the presence of a people where none was expected. San Nicolas Island is only 61 miles from the California mainland, but at the turn of the twentieth century, it remained largely unknown to most Americans. Travel to this most remote of the California Channel Islands was difficult because extreme weather patterns, including thick fog, were (and are) commonplace. Some accounts of the Lone Woman’s removal emphasize the mysteriousness of the place. They characterize the Lone Woman, before her "discovery," as a ghostlike figure who haunted the shores; they describe large bones on the island, "evidence" that the land was once inhabited by giants; or, for the avid fisherman, they remark on the overabundance of every conceivable marine animal and sea creature on and around the island’s shores. In tapping into the trope of wonder, these journalistic narratives mark the Americans who locate the Lone Woman as participating in the discovery (and hence possession) of her natal land, San Nicolas Island. Wonder and discovery, in this context, are inextricably linked.

—Sara L. Schwebel, PhD

February 1, 2016

1 See Lorenzo Veracini, Settler Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

2 On settler colonialism’s creation of Native refugees, see ibid.

3 On the capsizing of the Peor es Nada, see "Provincial State Papers: Benicia, Military, 1767–1845," LXXIX, p. 134 stamped (p. 73 penned), Archive.org, www.archive.org/details/168035972_80_2_2; "Provincial State Papers: Benicia, Military, 1767–1845, LXXXI, p. 227 stamped (p. 17 penned), Archive.org, www.archive.org/details/168035972_80_2_2; and "Departmental State Papers, 1821–1846 (1835)," IV, p. 69 stamped (p. 68 penned), Archive.org, www.archive.org/details/168036073_80_11_3. These three documents are transcriptions of the originals (which were lost in the San Francisco fire and earthquake of 1906), created for Hubert Howe Bancroft by Thomas Savage

4 Adele Ogden, The California Sea Otter Trade, 1784-1848 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1941): 134-35, 181.

5 Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of California, Vol. IV (San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft & Company, 1886): 376-77.

6 The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, Vol. XXXIII: History of Alaska, 1730-1895 (San Francisco: A.L. Bancroft & Company, 1896), 5, 25.

7 See Lydia T. Black, Russians in Alaska, 1732-1867 (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2004), xiv. An important exception to this trend is the work of one of Bancroft’s researchers, Ivan Petrov, who fabricated at least one Russian primary source in order to vilify the Spanish and Americans, as opposed to the Russians. See Kenneth N. Owens, ed., The Wreck of the Sv. Nikolai: Two Narratives of the First Russian Expedition to the Oregon Country, 1880-1810 (Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 2000): 77-88.

8 See, for example, Robert F. Heizer and Alan F. Almquist, The Other Californians: Prejudice and Discrimination under Spain, Mexico, and the United States to 1920 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), 11-12, 65-66.

9 See Diane Spencer-Hancock and William E. Pritchard, "Notes to the 1817 Treaty between the Russian American Company and Kashaya Pomo Indians," California History 59, no. 4 (1980/81): 306-13.

10 Kent G. Lightfoot, Indians, Missionaries, and Merchants: The Legacy of Colonial Encounters on the California Frontiers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

11 David D. Smits, "The ‘Squaw Drudge’: A Prime Index of Savagism," Ethnohistory 29, no. 4 (1982): 281-306.

12 Theodore Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, Vol. I (New York: The Current Literature Publishing Company, 1905): 121.

13 Constitution and Laws of the Grand Parlor Native Sons of the Golden West and Constitution for Subordinate Parlors (San Francisco: Frank Eastman & Company, 1901), 3. The Native Sons was founded in 1875.

14 See, in this archive, Travis Hudson, "Recently Discovered Accounts Concerning the ‘Lone Woman’ of San Nicolas Island," Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 3, no. 2 (1981): 187-99.

15 See Kent G. Lightfoot, Indians, Missionaries, and Merchants: The Legacy of Colonial Encounters on the California Frontiers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005) for an excellent discussion of the California example.

16 Ibid.

17 See Lee M. Panich, "Archaeologies of Persistence: Reconsidering the Legacies of Colonialism in Native North America," American Antiquity 78, no. 1 (2013): 105-22.

18 Susan L. Morris, John R. Johnson, Steven J. Schwartz, René L. Vellanoweth, Glenn J. Farris, and Sara L. Schwebel, "Nicoleños in Los Angeles: Documenting the Fate of the Lone Woman’s Community," Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 36, no. 1 (2016): 97-118.

19 Kenneth B. Kidd, Making American Boys: Boyology and the Feral Tale (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004): 3-7. Julia V. Douthwaite, "Homo ferus: Between Monster and Model," Eighteenth-Century Life 21, no. 2 (1997): 176-202.

20 Stephen Greenblatt, Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991): 14.

My thanks to Judy Kertész, PhD for rich discussion and her invaluable review of this essay.